Manahatta

Mary Kathryn Nagle

Aurora Theatre Company

Two American stories, four centuries apart, interlock in their telling, with characters, events, motives, triumphs, and tragedies strikingly similar in Mary Kathryn Nagle’s Manahatta, which premiered in 2018 at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Now in an intimately engrossing and enlightening production at Aurora Theatre Company, Manahatta links the lives of a modern, Native American family of the Lenape nation from Oklahoma with their ancestors who once lived on the island of Manahatta, now known as Manhattan.

Director Shannon R. Davis pieces their stories seamlessly in a continuous flow between geographies and eras as a cast of seven themselves switch from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries and back again, seemingly without a breath in between. The parallels of family dynamics and dilemmas as well as the false promises and deep prejudices they face are astonishingly similar, leaving the very real question hanging in the air of how much has truly changed when in fact, everything has changed between the 17th and 21st centuries.

Jane — a recent Stanford MBA graduate and gifted in financial mathematics — is about to join in 2002 the high-flying, manic-paced world of investment banking in Manhattan as a new hire of the prestigious Lehman Brothers. She is leaving behind in Oklahoma a mother, Bobbie — an elder in the present-day Lenape tribe of the Native American, Delaware Nation — as well as a sister, Debra, also a Lenape member of the Delaware Nation. As Jane begins to rip her way through the dog-eat-dog, male-oriented world of derivatives, her relationship becomes distant and occasionally strained with her family, who believe she is leaving too far behind her ancestral traditions and beliefs.

Such modern scenes quickly melt into the landscape of an island once known to its peoples as Manahatta at the time in the early 1600s when the Dutch East Indies Company was just arriving to a land populated only by the Native People, the Lenape families. On this small, multi-serving stage surrounded on three sides by us as audience, actors quickly switch to introduce us to another family — a young Le-le-wá-you, her sister Toosh-ki-pa-kwis-i, and her Mother, who is a revered and wise elder of the Lenape. Se-ket-tu-may-qua is a young Lenape man who loves Le-le-wá-you and who has learned to speak the tongue of the invading Dutch in order to trade furs with them.

Le-le-wá-you herself is ambitious, daring, and full of curiosity. She convinces her male companion to teach her the white man’s strange tongue. Le-le-wá-you too begins trading and bringing home much wampum to help provide for her sister and mother, both of whom are skeptical of her new ventures and of the white men.

Just as Jane’s career soars over the next, several years through a crazy rollercoaster course, Le-le-wá-you’s life too becomes more exciting as she gains confidence in her newly discovered skills of language and trade. Conflicts with both their more traditional families occur while each also has a young man who supports her groundbreaking career and who shows feelings of affection for her as a woman. Into each young woman’s life, ruthless, money-hungry, white men exert pressures and challenges.

And into each world, a major, earth-shattering shift occurs – life-and-history-shifting tremors stimulated by one word: Greed. For Le-le-wá-you, the cataclysmic shift comes when the Dutch trick her family and Se-ket-tu-may-qua to sell them Manahatta for a few trinkets and guns, with the Lenape people not understanding the concepts of ownership or the sale of land since in their tradition, the land is their home and not their property. Parallel in the storytelling, the 2008 financial collapse in the subprime mortgage market burns a flaming path right into the pristine offices of Lehman Brothers and into Jane’s once-meteoric career.

What is more striking in the two, unfolding stories than just the similarities of events and family dynamics are the attitudes and prejudices that we see born four hundred years ago and still playing out in our own world. Phrases by the Dutch of “they all look alike” or of a modern white man in New York letting slip “just off the reservation” reveal similar, inbred prejudices of those people much more native to the Americas than the speakers. When we see the Director of the Dutch East India Company as he tries to close the sale of Manahatta offer the Lenape family their first sips of brandy (promising “one of the greatest spirits we have”), we can only think of the lingering issues of alcoholism that so many Native American communities still suffer and the cheating promises that have made by white, greedy businessmen during the subsequent centuries. Throughout the two stories, such startling and sad mirroring of attitudes occurs – including an expensive wall advocated by the Dutch Director and then built in Manahatta to keep the Lenape away from the Dutch (i.e., the wall lending its names to Jane’s modern-day Wall Street).

To a person, the ensemble relating both tales is exceptional in portraying the persona of both eras. Livi Gomes Demarchi is unabashedly bold and determined as both Jane and Le-le-wá-you. Each is willing to use evident intelligence and insight to plow new grounds that a woman in her world has never been allowed to do. Like other cast members, her spoken tone, command of language, and general demeanor do not change as she shifts characters and eras, making the clear point that the young, Lenape woman of the 1600s has the same innate abilities and wherewithal of the one in the 2000s – a concept foreign to all those invading Europeans who for hundreds of years would continue to see Native Americans as inferior in intelligence, morals, and conduct.

As the mother of both scenarios, Linda Amayo-Hassan is especially striking in each as a rock of moral and cultural strength. There is profound depth in the soul and wisdom of both matriarchs. When either speaks, one wants to lean forth and not miss one word. The wry wit of Bobbie is particularly wonderful as she shocks her visiting banker/pastor, Michael (a kind but also calculating Victor Talmadge), with one-liners like, “We Lenape don’t drink tea [because if] we drink too much tea, we drown in our teepee.”

Oogie_Push is the second sister/daughter in both scenarios (Toosh-ki-pa-kwis-i and Debra, respectively) who is more conservative and cautious as well as more honoring native traditions than her sibling. Both portrayed sisters show tenacity and tenderness in helping her family through incredibly tough times.

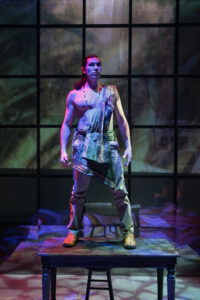

While Manahatta is to a large extent about two core families of women, it is the men surrounding them who offer great contrasts of honoring them or using/abusing them to the men’s capitalistic, self-centered interests. Ixtlán commandingly and convincingly is both Se-ket-tu-may-qua, the caring, supportive companion/mate of Le-le-wá-you and, Luke, Jane’s best friend in Oklahoma – each young man bearing similar, selfless characteristics and full support of his ambitious partner/friend.

Ixtlán’s portrayals are in great contrasts to the men Anthony Fusco portrays with palpable vengeance and venom: The cynical, demanding, ruthless egomaniac CEO of Lehman Brothers, Dick, and the equally greedy Director of the Dutch East India Company, Peter Minuit. Peter Minuit becomes the vicious perpetrator of murdering entire Lenape families (and of creating the term ‘red skin’ as the proof needed for settlers to attain bounty for killing the hated natives). While he does not murder people, Anthony Fusco’s Dick also watches lives ruined around him, readily willing to sacrifice whomever he must as soon as they are not helping his bottom-line and his own personal wealth during the collapsing days of Lehman Brothers.

Max Forman-Mullin serves as a kind of mixed-bag character in both stories, showing, for example, some fascination and initial compassion as the Dutch fur trader Jakob for the Lenape while also helping Peter Minuit dupe them into selling their homeland. As the CFO of Lehman, Joe, the man who initially hires Jane, has plenty moments of Wall Street cockiness and even bloodthirstiness; but he also has increasing moments of camaraderie and compassion for the talents that Jane so ably shows.

Reflective, square panels form a backdrop wall for Deanna L. Zibello’s mostly blank stage design. The panels emphasize the mirrored stories and histories of Mary Kathryn Nagle’s brilliantly conceived script. They also become the screen for Wolfgang Wachalovsky’s videos that facilitate shifts between the grasslands and forests of Manahatta and the modern realities of Manhattan. Particularly powerful in setting the moods and scenes of both centuries is the lighting design of Ray Oppenheimer. The gentle blending of colors of a landscape long gone contrast with the harsher lights and manners of a modern center of dodgy finances. Finally, the continual shifts in time and stories occur quite seamlessly through the flexible costume designs of Asa Benally.

As citizen of the Cherokee Nation and playwright, Mary Kathryn Nagle has instilled in Manahatta a deep and obvious respect for Native ancestors and ancestral traditions in the dual storytelling of two, too-similar time periods, providing a play that is educating and thought-provoking as well as emotionally memorable. Aurora Theatre Company’s one-hour, forty-five-minute (no intermission) production of Manahatta deserves full audiences during its well-directed, well-acted run as one family’s history becomes part of all our collective, national story.

Rating: 5 E

A Theatre Eddys Best Bet Production

Manahatta continues in live performance through March 10, 2024, and in streamed performances, March 5-10 in production by Aurora Theatre Company, 2081 Addison Street, Berkeley, CA. Tickets are available online at https://www.auroratheatre.org/ or by calling the box office at 510-843-4042.

Photo Credits: Kevin Berne